- Groucho Marx

I’m terrible with faces. You hear that a lot, and it sounds like an excuse: someone has forgotten you because they were uninterested last time they met you. But I honestly am. I can’t, at this moment,  mentally picture my girlfriend, my parents or anyone else I know. I’d recognise them instantly if I saw them, of course, but I know for a fact that other people can conjure a face up in their mind’s eye and describe it. As a kid, I’d infuriate my parents by asking questions throughout a film: I couldn’t follow the plot because I couldn’t tell the actors apart. Cartoons were fine. Even now, I sometimes have trouble with that. I got halfway through The Departed before I realised that the two main characters were actually played by different people - I’d mistaken Leonardo di Caprio for Matt Damon (still thought it was great, though).

mentally picture my girlfriend, my parents or anyone else I know. I’d recognise them instantly if I saw them, of course, but I know for a fact that other people can conjure a face up in their mind’s eye and describe it. As a kid, I’d infuriate my parents by asking questions throughout a film: I couldn’t follow the plot because I couldn’t tell the actors apart. Cartoons were fine. Even now, I sometimes have trouble with that. I got halfway through The Departed before I realised that the two main characters were actually played by different people - I’d mistaken Leonardo di Caprio for Matt Damon (still thought it was great, though).

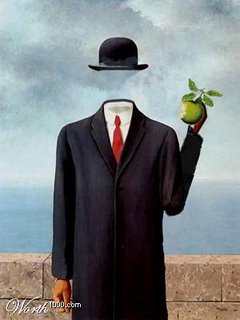

I don’t need any sympathy for this: it’s a minor inconvenience. But it’s occurred to me that maybe other people’s parietal and occipital lobes work slightly better than mine. That would tie in with the fact that somebody who had a vastly more intense version of the same problem was the man we know only as Dr P, who had a tumour in the right hemisphere of his brain and who was immortalised by Oliver Sacks as one of the greatest ever book titles, The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat.

I’d need three popular science books on my desert island: Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene (which is from before he became obsessed with God), Steven Pinker’s The Language Instinct, and this one. (I know you’re only allowed one book, but I’d have to come to some kind of arrangement with Kirsty Young.) It’s a collection of case studies - but written in a warmer style than you usually expect from case studies - of some peculiar neurological problems. It gives you the uncomfortable feeling that you’re reading it for the wrong reasons. Sacks writes in the hope that “others might learn and understand, and, one day, perhaps be able to cure”. But it’s a freak show, too. The man who’s believed it was 1945 ever since it really was 1945 is just as weird and wonderful as The Amazing Bearded Lady or The Man Who Eats Metal or whatever. And just as much of a draw: Sacks’s book has been made into a successful play and an operetta and has inspired other works of art as well, including - and of course this is the real accolade - an album by Travis.

But he achieves his aim, nonetheless. Maybe you start reading for the same reason you watch a TV programme called When Plastic Surgery Goes Wrong, but you can’t help thinking in a different way after you’ve come into contact with Sacks’s writing. For example, when he visits Dr P, he sees the man’s paintings: the early ones realistic and the late ones abstract. He realises that this progression is evidence for the advance of the disablity, but also sees the possibility of artistic merit:

Perhaps, in his cubist period, there might have been both artistic and pathological development, colluding to engender an original form; for as he lost the concrete, so he might have gained in the abstract, developing a greater sensitivity to all the structural elements of line, boundary, contour - an almost Picasso-like power to see, and equally depict, those abstract organisations embedded in, and normally lost in, the concrete…

I’m not a Picasso fan, but after reading that passage I find it possible to see some strange shapes in faces, which I can’t see when I’m looking at them as faces. Try doing it with pictures where the face is upside down or distorted, so that its faceness doesn’t jump out so much. Perhaps it’s even true that I’m better at it than you are. Which wouldn’t be as handy as remembering whether I’ve met you before, of course.

5 comments:

Something which I have found as I grow up (I'm not yet at the age where I stop growing up and start growing old) is that actors can have incredibly minor roles in films and yet I'll remember them when I see another of their performances. This is combined with a frequent inability to remember actual film titles or actors' and characters' names. Watching film and TV drama at home consists of a long string of 'That's that chap that was in the one about the writing table that sent letters to the past', or 'She was the Bennet daughter, the boring one, you know the one who reads all the sermons, in the BBC Pride and Prejudice from the mid 1990s'. And yet, when I meet real people for a second time, I often don't remember them. And I doubly don't remember their name.

I've decided that rather than a psychological thing it is because I'm not quite brave enough to continually look at someone's face when talking to them. Often you can't due to practicality. For example, if you are walking together it is not advisable to study their face in great detail. This is combined with the fact that if we are engaged in conversation, I will mainly be focussed on a single feature of their face, be it mouth or eyes.

There is also the possibility that I've decided it's not a psychological thing because I don't want to think that celebrity is enough of a factor to imprint someone on my mind. Even if they were just in that episode of Casualty with the guy who skewered himself on his dog.

My favourite bit of the book is when the group of patients who have lost the ability to understand language are laughing at the television. They don't understand a word that the politician on screen is saying, but they can tell from his body language that he is lying.

I sympathise because I have the same problem recalling faces. It is worse when I meet someone and then kiss them on the same night because afterwards I feel like I really must remember their appearance but I just can't do it.

Thirty people individually spent about half an hour with me looking at faces for my final year research project on face recognition and afterwards, I could hardly identify any of them when I bumped into them in the street.

As for Damon and di Caprio, I've always got them muddled up and I can't believe the stupidity of someone for casting them in the same film.

Oh, I wouldn't go that far. The film got a lot of mileage out of making the two characters' lives parallel. It was one of those there-but-for-the-grace-of-God storylines.

They don't look the same at all. Not to me, anyway. But then I'm quite good at faces. You should see my beard...

Post a Comment